Publication

The PHEV Paradox

Plug-in hybrids, a combination of two engine systems in one vehicle, are enjoying rising popularity both in demand – an annual doubling in the growth rate of registrations in Germany no less – and in manufacturers’ offerings. We predict that in the next few years there will be a significant absolute increase in PHEV vehicles. Why this is and whether this development is ecologically sustainable, how it is currently being promoted by the public and in the media, these are the topics we will address here.

On the demand side

The government offers tax incentives for vehicles which have an electrical operation (a halving of the benefit-in-kind). Furthermore, there is a significantly lower vehicle tax (approx. factor 51) as a result of the carbon footprint, as well as lower petrol consumption in test cycles. These are the obvious advantages to plug-in hybrids. At the same time, the customer can use a PHEV for emission-free travel, which for many also presents an argument in favour of purchasing. These advantages are offset by the higher purchase or leasing costs (up to 10%3) and no real variable cost advantage (comparing kWh and fuel costs) in comparison to diesel or petrol vehicles – good reasons to decide against a plug-in hybrid.

In addition, there are only about 20,000 public and semi-public charging stations – from energy companies, car parks and car-park operators, supermarkets and hotels – available throughout Germany. The federal government’s targeted goal of a million electric cars by 2020 would, however, require up to 70,000 public charging stations. A figure that is completely unrealistic at present – if the target is to hold up, we must expect a clear trend towards PHEVs, as this is the only way that the dependency on charging stations can be reduced while at the same time pursuing the desired goal.

On the supply side

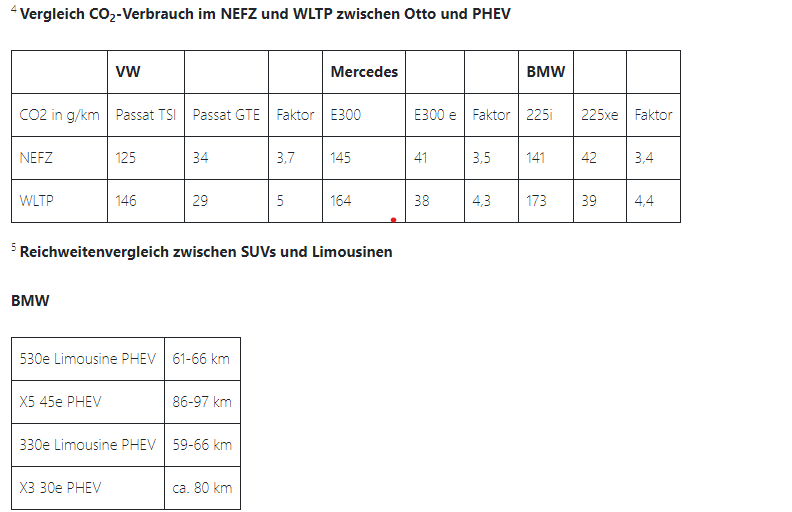

The reduced offering of plug-in hybrids on the part of manufacturers was, in the past, an expression of the discrepancy described between the advantages and disadvantage of alternatives to petrol and diesel vehicles. This will change dramatically in future – the CO2 fleet thresholds will make it possible. PHEVs are the crucial, and at the same time the only way for German OEMs to significantly reduce their fleet averages. In addition to the CO2 consumption, which is already lower in test cycles4, all vehicles registered in 2020 with a CO2 value of <50 g/kmwill be doubly rated in the valuation of averages (1.66 in 2021 and 1.33 in 2022). Following the introduction of the WLTP, a “utility factor” will also apply for PHEVs; this factor represents the portion of journeys which are travelled electrically and has an impact on the average value of PHEVs, which are therefore emerging as more advantageous compared to internal combustion engines. The CO2 fleet average – stipulated individually for each OEM – is based on the average weight of the entire vehicle fleet. Accordingly, with a higher average weight, OEMs can prepare themselves for a higher permitted CO2 fleet average (weight increase of at least 10%2). This advantage of PHEV new registrations will not, however, pay off until the following year, as the weight average is calculated on the basis of the average of the previous 3 years.

A further advantage on the manufacturing side is that, in comparison to fully electrical vehicles, PHEV vehicles utilise the manufacturer’s engine factory to capacity. The capital investments made and production resources can continue to be used.

Moreover, the combined motor technologies offer leverage to be able to offer SUV models in larger numbers. SUVs have the advantage of offering more installation space for cells and thus facilitating an increased range (approx. 30%5). Consequently, SUVs will continue to remain attractive for purchasers and manufacturers and therefore no portfolio adjustment will be needed.

Summary

In many ways, the development of the automotive market in the direction of PHEVs is currently, subsidised or supported by the government, directly or indirectly. Having said that, with regard to the topic of sustainability, the PHEV is a sub-optimal solution. The carbon footprint of electrified motor technology is far worse along the supply chain that that of internal combustion engines and the PHEV not only combines two engine systems with each other, it also combines their carbon footprints: the bad of the petrol motor over the duration of the service life with the bad of the electrified engine in the supply chain – we call that the PHEV paradox.